Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Kent Nishimura / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

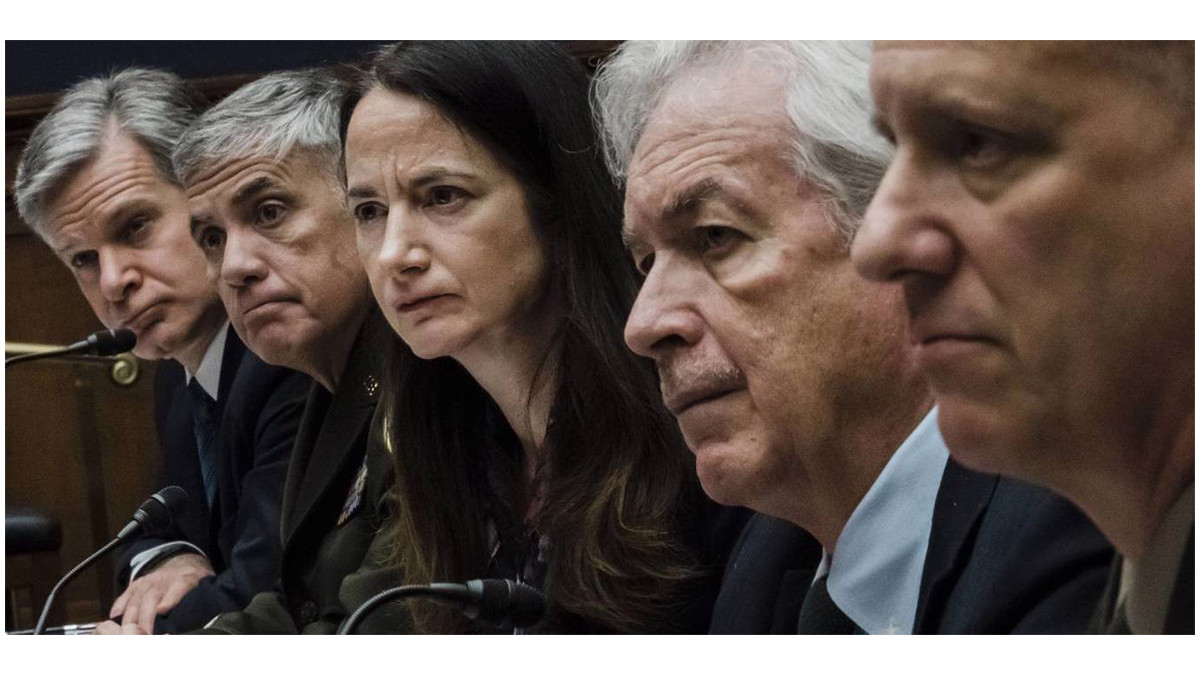

ATLANTA –Last month, when US National Intelligence Director Avril Haines presented the intelligence community’s annual threat assessment to the Senate Intelligence Committee, committee members praised her for the “excellent work” leading up to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and for “continuing to keep us informed.” To the US intelligence community’s credit, and to Russian President Vladimir Putin’s chagrin, US senators weren’t the only ones kept informed. The rest of the world was, too, thanks to thorough strategic US intelligence disclosures.

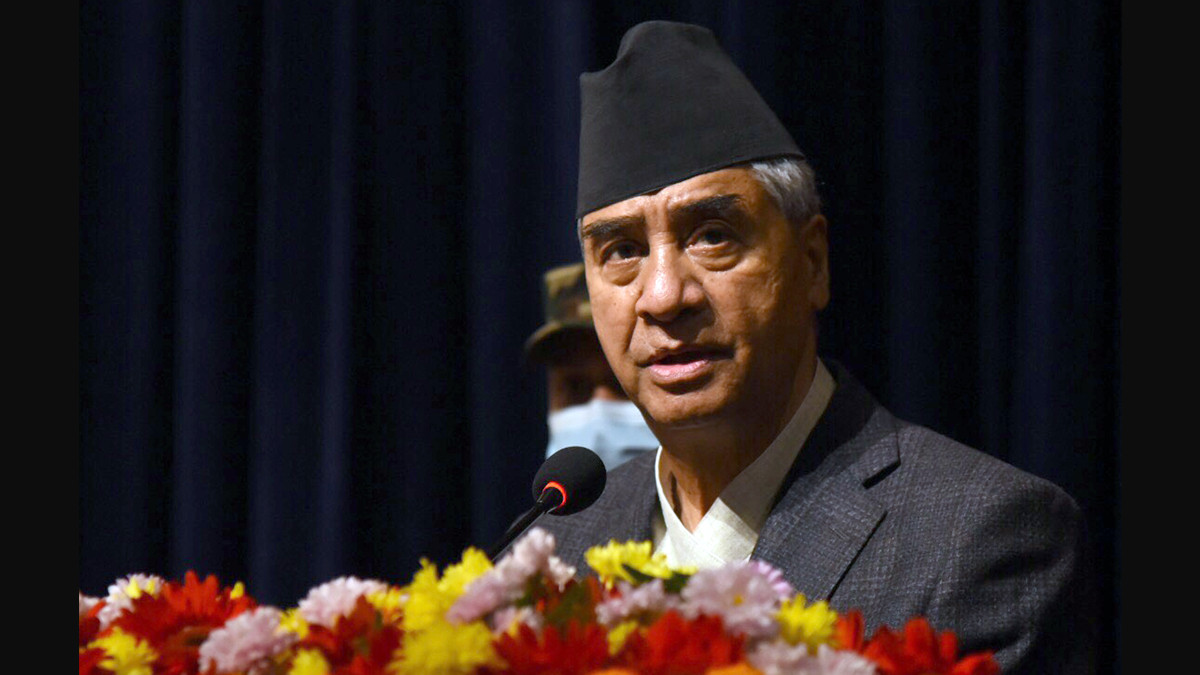

Making intelligence public is more art than science, and spies and analysts have struggled to master it. But when it comes to Ukraine, CIA Director William Burns deserves recognition for changing how the agency thinks about revealing its secrets. A former ambassador to Moscow, Burns told the Senate committee that, “In all the years I spent as a career diplomat, I saw too many instances in which we lost information wars with the Russians.”

That experience has now paid off. For months before Putin’s invasion, the intelligence community played against type, declassifying information and analyses that previewed Russian preparations and intentions. The reports discredited ostensible provocations (“false flags”) and warned about Russia’s military build-up. Dismissed by Kyiv and Moscow at the time, the facts and forecasts hit the bull’s-eye. As Russian forces now sink deeper into a new quagmire, US intelligence agencies should lean into this strategy.

To be sure, the intelligence community has long regarded publicizing secrets as a heresy, and the duty to protect sources and methods remains sacred, for good reason. Disclosures can threaten the products of multi-billion-dollar technical collection systems, not to mention the lives of human sources reporting from inside hostile regimes. But the war in Ukraine shows why the intelligence community’s assessment of these risks should be recalibrated. In today’s media environment, the imperative to debunk disinformation is growing, as is the need for intelligence to meet the challenge.

Consider this year’s annual threat assessment. Completed in February, before Russia’s invasion, it doesn’t address the invasion’s global implications and the West’s response (though much of its unclassified analysis does remain valuable). In the weeks ahead, Haines and the intelligence chiefs therefore should release a rebooted analysis, which would provide the public with valuable insights into the decisions being made in Washington, other NATO capitals, and elsewhere.

The prospect of a long struggle in Ukraine points to why this is needed. Among Putin’s major miscalculations was the assumption that Russian forces would walk over Ukraine’s defenses, topple the Ukrainian government in Kyiv, and cow the population. It now remains to be seen how long the Ukrainian resistance will last, what Ukrainians’ reaction to Moscow-installed mayors and other officials will look like, and how Putin will respond when sanctions really start to take their toll. But whatever happens, public knowledge of intelligence that validates facts on the ground will be crucial for decision-makers.

Moreover, despite the Russian army’s failures in Ukraine, Moscow’s information warriors have shown no sign of relenting. From Putin’s claim that he is “denazifying” Ukraine to the Kremlin’s revival of Soviet-era howlers about US bioweapons labs, there is more than enough Russian propaganda to counter, especially now that many US politicians and talking heads have started parroting the same talking points.

The spies and analysts who helped upset Putin’s pre-war propaganda offensive should continue to make full use of the tools at their disposal. As with the intelligence community’s unclassified briefings to Congress, intelligence insights can be publicized without revealing sources, methods, or even secrets. After all, intelligence analysis can and often does make use of open-source information from commercial satellites, citizen journalists, activist analysts, social media, and instant messaging.

These channels offer a mother lode of the kind of data and reporting that once only classified collection could provide. Matt Freear, a former British Foreign Office spokesman who specializes in strategic communications, notes that, “In the build-up to the invasion of Ukraine, it was publicly available satellite imagery shared online and used in news reports that gave credence to official warnings…about Russia’s intended aggression.” Other recent examples include Bellingcat’s investigation into Russia’s role in the downing of Malaysian Airlines Flight 17 over Ukraine in 2014 and the crowdsourcing of images exposing Syria’s chemical-weapons attacks in 2018.

Freear correctly adds that the value of open-source information hinges on its credibility, and that intelligence officers and governments should always proceed with caution when using it. But like journalists who report on open-source findings from third parties, intelligence agencies can use their own resources to help validate what others are saying. In this way, their own analyses can help to sort truth from fiction in the increasingly important information war.

A good example of such collaboration is the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency’s Tearline Project, which focuses on important but under-reported stories, in partnership with non-profit research organizations and think tanks studying an array of environmental, economic, and other issues. Most recently, the agency has helped to provide real-time support via unclassified satellite imagery to news organizations whose journalists are reporting from the front lines in Ukraine. If a picture is worth a thousand words, this effort is bringing ample power to bear against Putin’s disinformation campaign.

Kent Harrington, a former senior CIA analyst, served as national intelligence officer for East Asia, chief of station in Asia, and the CIA’s director of public affairs.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2022.

www.project-syndicate.org

Kent Harrington

Kent Harrington